Outer-Body

42 Victoria St, Te Aro, Wellington

Restrictions

Websites

Listed by

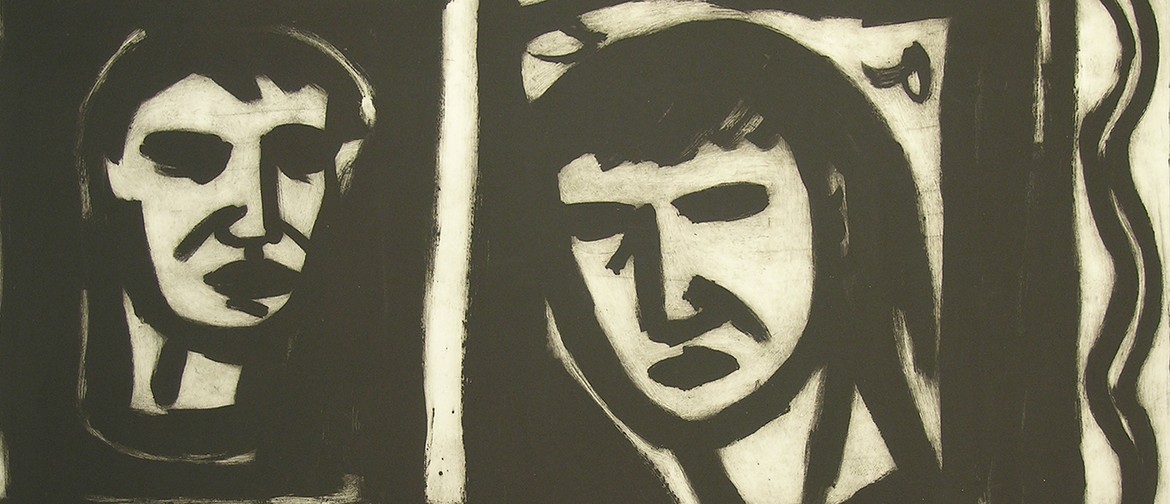

The act of capturing the human form is at once intimate and elusive. The specific contours of a face, the familiar outline of shoulders, the nape of a neck, the characteristic crossing of one limb over another. While these features circumscribe the outer limits of the corporeal body, they also act as signifiers to that which remains unseen – the complex interior world of individual histories, heartbreak, imagination, and spirituality.

Outer-Body brings together works from numerous artists, spanning various modes and many decades. More traditional notions of portraiture – from artists including Heather Straka, Robin White, Toss Woollaston, Jeffrey Harris, and E Mervyn Taylor – are situated alongside others that push at the peripheries of the medium and into the realm of the abstract and the sacred.

Derek Cowie’s suite of paintings on cracked plaster borrows from German-Swiss Renaissance artist Hans Holbein the Younger, whose characterful style beckoned a new era of image politics. Cowie re-imagines Holbein’s portraits as though they have been found in the rubble of a post-apocalyptic world, highlighting the perversity of allocating value to art and objects in the face of environmental devastation. Emily Wolfe’s paintings of Delft figurines have similarly European origins, here depicted having suffered critical damage on their journey to join the artist’s personal collection, and we can’t help but anthropomorphise and impose narrative upon the inanimate porcelain figures.

Sculptural works include Hannah Valentine’s bronze Bodyform (if only you had the nerve) for which the artist cast lengths of wax more than double her height, using her own physical form to dictate the limits of the sculpture. Turumeke Harrington’s For Hineateao, no U-turns acts as both tribute to the goddess of the underworld and as self-portrait (the T-U-I forms alluding to the artist’s nickname) weaving together Harrington’s whakapapa with artists who have paved the way for her practice.

Ben Cauchi’s ambrotype Hovering Cloth points to an invisible body – the artist working through historic photographic processes to explore our relationship to photography, collapsing associations of truth and objectivity through the illusory image. Mark Adams’s photographic triptych 9.7. 2005. At Tokatoka, Northern Wairoa River documents and memorialises past lives through the site of the cemetery on the Northern Wairoa River in Northland, a landscape inscribed with complex cultural, ecological, and historic significance for both Māori and Pākehā.

Some works occupy a more fanciful sphere, redolent with the experience of both making and experiencing art, where one is pulled into a particular moment or alternate orbit – such as Elizabeth Thomson’s dreamlike Iberis, where a figure walks through a strange lunar-like landscape, or in Cerith Wynn Evans’s fleeting image of a yellow-breasted bird perched atop the head of an archangel in the Oscar Niemeyer designed Metropolitan Cathedral of Brasília.

Through these works, a conceptual line forms and sharpens our understanding of collective humanity, and our enduring pursuit of intellectual, ethereal, and outer-body experience.

Log in / Sign up

Continuing confirms your acceptance of our terms of service.

Post a comment